Hyperacusis Research president Bryan Pollard spoke to doctors and audiologists at the University of Iowa’s 25th Annual International Conference on the Management of the Tinnitus & Hyperacusis Patient. The topic of Bryan’s talk was “What’s life really like with hyperacusis?”

Bryan focused on three key aspects of hyperacusis:

- The Patient’s Reality

Bryan told the story of a hyperacusis sufferer who has tried many approaches to improve, including Tinnitus Retraining Therapy and round window reinforcement surgery. This patient’s story highlights the reality for some sufferers. They continue to face regular pain from everyday noises. Research is needed to find ways to help these individuals improve and to ultimately find a cure. - The Patient’s Visit

Bryan described the patient’s perspective with a typical visit to audiologist, filled with noise hazards that few would even think of. These hazards included travel to the office, noisy waiting rooms, squeaky doors, loud speaking voices and even audiological testing that puts noises directly into a vulnerable ear. - The Patient’s Future

After highlighting the growth in research for hyperacusis, Bryan discussed some key findings from the Sanford CoRDS hyperacusis survey. The main focus of the findings related to pain and setbacks. 66% of patients experience continuous or daily pain, which results largely from new noise exposures. For 25% this pain last 5 to 24 hours and for 28% it lasts days. For the majority, it takes several days to recover from a setback.

Bryan concluded by stating that hyperacusis with pain represents a type of hyperacusis that must be handled differently from loudness hyperacusis. Clinicians should ask essential questions to determine if the patient experiences pain with new noise exposures. They should also ensure that the patient’s approach to noise exposure helps to mitigate new cycles of pain by limiting exposures to those below the pain level. A gradual approach is needed so the patient does not worsen.

Studies on Treating Hyperacusis, Craig Formby, PhD, Distinguished Graduate Research Professor, University of Alabama

Craig Formby gave the keynote talk on Hyperacusis. He started by describing the 4 basic hyperacusis types, loudness hyperacusis, annoyance hyperacusis (misophonia), fear hyperacusis (phonophobia), pain hyperacusis.

For loudness hyperacusis, Craig pointed to the first classification of dynamic range hyperacusis from Jastreboff and Hazell’s (1993) definition of ‘”sensitivity to sound/hyperacusis” as a dynamic range less than 60 dB. The chart below outlines the categories Craig has used in his clinical research on hyperacusis.

| Hyperacusis | Dynamic Range | Loudness Discomfort Level |

| None/Negative | 60 dB or greater all frequencies | 95 dB or greater all frequencies |

| Mild | 50‐55 dB at any frequency | 80‐90 dB at 2 or more frequencies |

| Moderate | 40‐45 dB at any frequency | 65‐75 dB at 2 or more frequencies |

| Severe | 35 dB or less at any frequency | 60 dB or lower at 2 or more frequencies |

Craig then reviewed the clinical evidence supporting treatment, starting with the effects of sound therapy from TRT. University of Maryland Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Center (UMTHC) TRT treatment records from 1992-2006 were reviewed for patients using noise generators (NG’s) for low-level sound therapy (Formby et al., 2007). The analyses revealed:

– Large and consistent incremental shifts in post-treatment LDLs (> 10 dB).

– Concomitant subjective improvements in sound tolerance with expansion of the listener’s dynamic range.

– Potentially new opportunities for enhancing aided listening among hearing-aid users with reduced sound tolerance/dynamic ranges.

A key feature of the talk was the presentation of the following work: A Sound Therapy‐Based Intervention to Expand the Auditory Dynamic Range for Loudness among Persons with Sensorineural Hearing Losses: A Randomized Placebo‐Controlled Clinical Trial, Craig Formby, Ph.D., et al. Seminars in Hearing, Vol. 26 (2), 2015

The goals of the trial were to: (1) verify Hazell and Sheldrake’s sound‐therapy‐protocol treatment results for hyperacusis; and (2) extend the treatment to problematic hearing‐aid users with reduced LDLs and elevated hearing thresholds, which diminished their dynamic range.

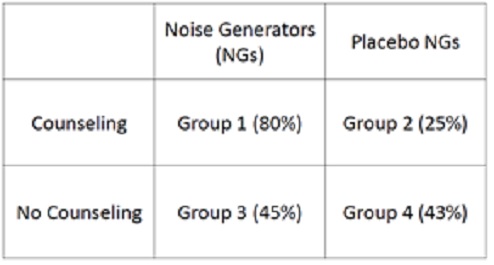

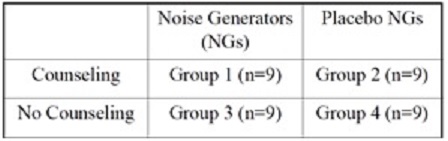

The study was designed as randomized, placebo controlled (for sound therapy) clinical trial as shown in the diagram. Investigators were blinded to NG group assignment, but not the counseling assignment.

The study was designed as randomized, placebo controlled (for sound therapy) clinical trial as shown in the diagram. Investigators were blinded to NG group assignment, but not the counseling assignment.

Primary Outcome Measures for Treatment Graduation

Loudness discomfort level (LDL) judgments and categorical loudness judgments (ContourTest) were measured at baseline and then monthly over a treatment period of 5-12 months. Graduation from treatment required ≥ 10 dB incremental changes in the LDL or “uncomfortably loud” (UCL) categorical judgments at two consecutive monthly visits

Outcome of the Trial

80% of subjects with a reduced dynamic range benefited from the full intervention implemented with noise generators and counseling (e.g. meaning they had ≥ 10 dB improvement). Some patients improved with partial treatment, but on average, ≤ 45% of the subjects in the alternative intervention groups received a treatment benefit.

Hyperacusis Hybrid Device

Dr. David Eddins from the University of South Florida highlighted a key new effort Hyperacusis Research is supporting – the development of a hyperacusis hybrid device. This proposal (see description here) involves a dual device that suppresses loud noises above a certain threshold and also incorporates a sound generator for treatment. This device offers, in a single flexible instrument, a promising transitional intervention to sound-enriching therapy with loudness-suppressing compression processing that provides improved audibility and a broader dynamic range, without opposing the therapeutic effects of enriching sound therapy. The study includes a well-designed clinical trial which will be centered at the University of South Florida. Please contact us if you would like to participate and can travel to Tampa, Florida.

Other Highlights from the Conference

Tinnitus was covered in an in-depth manner by a variety of speakers. Professor Rich Tyler of the University of Iowa described causes, mechanisms and model of tinnitus as well as measurement approaches. Rich pointed out at least three possible mechanisms associated with the auditory cortex:

- Increased spontaneous activity

- Synchronous activity across fibers

- Over‐representation of some area

He further pointed to several findings indicating likely involvement of the Amygdala (part of the limbic system within the brain which is responsible for emotions, survival instincts, and memory).

For tinnitus assessments, Rich favored the Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire. Rich cautioned that some assessments contained too many quality-of-life questions, which may cause an over-representation of non-tinnitus related impacts of certain treatment approaches.

Rich summarized his clinic’s approach to tinnitus, which is called Tinnitus Activities Treatment. You can find the details of this approach on their website.

The descriptive term “activities” is used because there are homework assignments with each counseling session. Rich focuses on four key areas of tinnitus impact with patients: thoughts and emotions, hearing, sleep, concentration. A unique feature of his approach is the use of pictures and diagrams in counseling. See the introductory set here. An important point is that Rich prefers to call this work with patients “management” of tinnitus and not treatment because treatment implies a cure or elimination of the ringing.

The descriptive term “activities” is used because there are homework assignments with each counseling session. Rich focuses on four key areas of tinnitus impact with patients: thoughts and emotions, hearing, sleep, concentration. A unique feature of his approach is the use of pictures and diagrams in counseling. See the introductory set here. An important point is that Rich prefers to call this work with patients “management” of tinnitus and not treatment because treatment implies a cure or elimination of the ringing.

Several talks were given summarizing the recently completed Tinnitus Retraining Therapy trial. Roberta Scherer, Director of the TRTT Data Coordinating Center at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health spoke on the overall trial design. The TRTT is a randomized, placebo controlled, multi‐center trial that aimed to test the efficacy of TRT versus standard of care treatment in individuals who have self perceived debilitating tinnitus and are seen in US military hospitals. The three groups are described in the table below.

| Group | Counseling Type | Sound Generator | Environmental Sounds |

| TRT | Directive | Full Sound Generator | Encouraged |

| Partial TRT | Directive | Placebo Sound Generator | Encouraged |

| Standard of Care | Standard of Care | None | Encouraged |

The Placebo Sound Generator worked by initially producing an audible white noise and then gradually fading out over 30 minutes (based on the idea that most people don’t notice the white noise after a brief period of time). The Standard of Care was described in another talk. The clinical sites included Walter Reed Military Medical Center, three Naval Medical Hospitals, and two other military medical centers. Eligibility Criteria included continuous, chronic, subjective tinnitus of > one year, a Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ) score 40 or greater (moderate impact of tinnitus) and unaided hearing sensitivity bilaterally within audiometric range from normal to mild limits. Clinical visits included two treatment visits and follow-up visits at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months. There were a total of 151 study participants.

Roberta described the results as surprising. All three groups improved significantly and were statistically matched in results. After starting TQ scores around 55, each group improved as follows: Standard of Care: -16.5, Partial TRT: -19.0, TRT: -18.2. Most all of the improvement occurred in the first 3 months for all groups, with a leveling off in the last 12 months. Other measurement methods such as the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory showed similar results. It is helpful to now have a validated clinical trial showing the benefit of TRT for tinnitus, although more research is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms that also enable a placebo TRT and Standard of Care to show equivalent benefits.

Sue Ann Erdman, MA, CCA-A from Audiologic Rehabilitation Consulting and Counseling described the details of the TRTT Standard of Care group. The Standard of Care implies state of the art, evidence based clinical care. In the case of tinnitus this had to be defined for the purpose of the trial. This work began with a survey of military audiologists and practice guidelines established with ASHA. A patient centered care script was developed for trial audiologist to utilize with participants.

Sue provided a brief background on patient centered care. As applied to the TRT trial, a key difference in the Standard of Care group is that the counseling was not directive. That is, information was provided with the patient making an interpretation of the information rather than the clinician directing the patient’s plan in detail. It encouraged a holistic approach to management, with an emphasis on the clinician demonstrating empathy. Collaborative decision making is the pinnacle of patient centered care. Environmental sound devices this group used included fans, music or home white noise devices. This standard of care approach was shown to be as effective as TRT in the trial.