By Dr. Kelly Jahn

Hyperacusis Research spoke with one of our scientific advisors, Kelly Jahn, AuD, PhD, of The University of Texas at Dallas, who recently published two important papers: One on the variability in hyperacusis knowledge by audiologists and one on the patient experience of pain hyperacusis.

Dr. Jahn runs the Neuroaudiology Lab at The University of Texas at Dallas, working on diagnostic tools and treatments for hearing loss and hyperacusis.

As told to Joyce Cohen and Owen Llodra

Like many people, I was never educated about the dangers of noise exposure. I played flute in the school band for many years and had no education on participating safely. Once I learned about audiology and became involved in hearing research as a college student, I started to worry about my hearing health. Now, I know that while I do not have hearing loss as measured by standard clinical tests, I am unable to hear ultra-high-frequency sounds, and I do not have measurable otoacoustic emissions (i.e., faint sounds produced by healthy cells in the inner ear). This suggests that I have experienced some subclinical damage to my ears. If I weren’t in this profession, I wouldn’t know that I have subtle signs of noise damage. I do not know whether or how much this will worsen over time as I get older.

Throughout my time in the field, I have noticed that it is difficult to convey the importance of protecting one’s hearing. Loud noise is socially acceptable in many places (e.g., restaurants, concerts, nightclubs, sporting events) and if someone has a temporary hearing loss or tinnitus after noise exposure, their hearing often returns to normal. It is hard for young people to grasp that there can be cumulative damage over time after repeated exposures.

I wanted a career that combined science and math with helping people. In college at the University of Connecticut, I worked as a research assistant in a Hearing Conservation Laboratory (where I first learned about noise exposure and its effect on hearing). I liked it so much that I went to Vanderbilt University to train as a clinical audiologist. Over time, I realized that I was more interested in research than clinical work. I felt that I could use my skill set and interests to impact more people through research.

Traditional Testing Methods Can Cause Excruciating Pain to Hyperacusis Patients

I focused primarily on cochlear implant research as an AuD (Doctor of Audiology) student and, subsequently, as a PhD student at the University of Washington. I shifted gears when I began my postdoctoral fellowship at Harvard Medical School and Mass Eye & Ear. There, I focused on measuring behavioral and brain responses to sounds to better understand the underlying mechanisms of loudness hyperacusis and tinnitus.

Through that experience, I realized that traditional audiology testing methods (i.e., when we present sound and ask a person to respond to the sound) do not work for people who suffer from severe pain hyperacusis. Scientists and clinicians often overlook these patients because our traditional sound tests can lead to excruciating pain in the ears, head, and neck. It is therefore very challenging to design a hearing research study to explore why sound causes tremendous pain for these individuals.

Because of these research challenges, I was curious about what happens when these patients seek professional guidance at a clinic. We went through all audiology clinic records at Mass Eye & Ear dating back to the year 2000 to see if we could gain some insight into this question. We were able to identify interesting trends in the hearing profiles of adults with hyperacusis, but it proved very difficult to find detailed information about what clinicians are doing with these patients aside from a regular hearing test.

The clinicians did not consistently ask about hyperacusis, so we could analyze records only of the patients who mentioned hyperacusis themselves during the appointment. Even then, there was little-to-no indication of follow-up or special testing beyond a regular hearing test. That made me wonder: How do clinicians diagnose hyperacusis and what testing protocols are they using in the clinic?

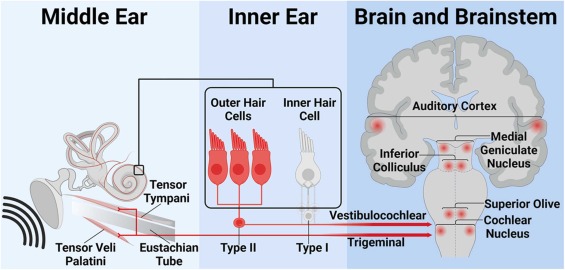

Potential mechanisms for pain hyperacusis (published in Jahn et al., 2025). Courtesy of Dr. Kelly Jahn.

Audiology Doctoral Programs Provide Five Hours — at Most — of Hyperacusis Education

In 2023, we surveyed 102 audiologists across the U.S. to see what they knew about hyperacusis and what testing they administer to these patients. At the time of the study, there were 79 Doctor of Audiology programs in the U.S. (there are now 80 programs). Thirty-eight programs had a tinnitus course, with just 14 of those providing information about sound intolerance to some degree. Thus, most of our survey respondents reported five hours or less of hyperacusis education. Most of the time, they had to seek out this education on their own (i.e., the education was not provided as part of their graduate program).

We found that few audiologists knew about the different hyperacusis subtypes, and the way they defined hyperacusis varied quite a bit. The audiologists surveyed often thought about and assessed hyperacusis differently. Only a few said it involved pain, and some said it’s a mental health condition. The most common tool used to diagnose hyperacusis was the Loudness Discomfort Level (LDL) test; however, there was no consensus on the appropriate way to administer this test, what diagnostic information it provides, and what criteria should be used to determine if a patient actually has hyperacusis or not.

I question whether LDLs are clinically useful if they are not measured in a systematic way and if we do not have clinical guidelines for diagnosis. It is also unclear how an LDL measurement translates to the person’s lived experience with hyperacusis. How hyperacusis impacts a person’s quality of life is likely more important than an LDL measurement.

That being said, if a provider or a researcher needs to monitor changes in sound sensitivity over time, they do need to have something to measure. Currently, LDLs and questionnaires are two of the only measures that we have to work with. Regardless of what testing the clinician decides to do, I believe that the tests should have a clear purpose, and that they should not cause undue stress or discomfort for the patient. It is important to acknowledge that some patients have reported increased pain after LDL testing. This underscores the importance of carefully selecting tests that will aid in diagnosis and management. Patients should consent to all testing that is performed.

Every Single Participant with Pain Hyperacusis Found a Lack of Support from Healthcare Professionals

Our survey clearly highlighted the need for more education and awareness of the different subtypes of hyperacusis, especially loudness versus pain. I first learned about pain hyperacusis when I began attending Hyperacusis Research, Ltd. meetings during my postdoctoral fellowship (around the year 2020). I realized that there was barely any literature that distinguished loudness from pain hyperacusis at the time. I became very interested in speaking with people who actually have this condition to learn more about their experiences.

The Internet and social media have been really beneficial for connecting with individuals who suffer from severe forms of pain hyperacusis who cannot visit the research lab to participate in a study. I will personally never know exactly how it feels to experience pain hyperacusis, so connecting with these sufferers is critical so that I don’t lose sight of the debilitating nature of sound-induced pain.

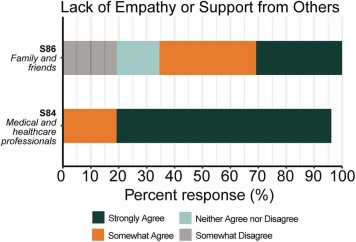

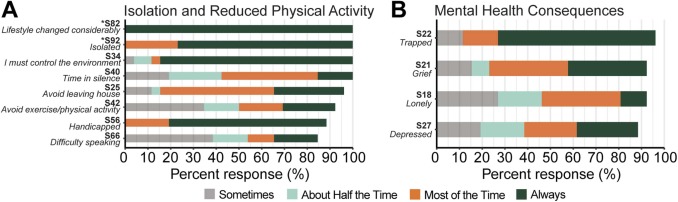

By virtually interviewing and surveying a group of 32 patients with severe pain hyperacusis, we were able to learn just how life-altering the condition can be. It was eye-opening for us to learn that every single participant felt a lack of empathy and support from healthcare professionals, suggesting that the way the condition is approached in the clinic may be detrimental to their well-being in some ways.

When a patient comes to the clinic, the provider assumes their goal is not to stay in their quiet home, but rather to go into the world and live a more active life. This assumption is well-intentioned but fails to recognize the complex relationship that someone with pain hyperacusis has with sound. Severe pain hyperacusis is a crippling condition for many individuals. It is understandable that someone who has experienced setbacks due to sound exposure would be hesitant to jump back into a world of sound.

To develop more of a mutual understanding, the provider should ask about the patient’s goals and what they have tried. If avoiding sound is what makes them feel better, we need to meet them where they are and develop a plan that considers their personal experiences and preferences.

Percentage of patients who found a lack of empathy or support from others (published in Jahn et al., 2025). Courtesy of Dr. Kelly Jahn.

Family Support is Critical for Such a Life-Altering Condition

Many participants in our pain hyperacusis study said that healthcare professionals have told them to “get over it” or to avoid sound deprivation at all costs. There are multiple carefully controlled research studies that have shown changes in loudness perception following constant earplug use for a 1- to 2-week period. These studies are very informative from a scientific perspective and have helped researchers generate hypotheses and learn more about the ear.

However, it is also important to acknowledge that these studies typically include adults with normal hearing who do not suffer from debilitating burning or stabbing ear pain. The sounds used in those studies (typically pure tones) are also very different from real-world sounds like a honking horn or a barking dog. It is unsurprising that a blanket suggestion to avoid ear protection may not be an appropriate first step for someone who suffers from pain hyperacusis. Again, we need to meet these patients where they are and take the time to understand their lived experiences, concerns, and goals.

We do not yet have strong scientific evidence for interventions that specifically target pain hyperacusis or proper recommendations for ear protection or sound avoidance in this population. Regardless of the absence of an evidence-based treatment or cure, audiologists should listen to what the patient is experiencing, empathize with the patient, and see if there are challenges they can address, such as making appropriate referrals (e.g., general pain specialists) or improving familial awareness.

Family and social support is critical for individuals who suffer from chronic medical conditions, and our participants indicated that it is very difficult for their family and friends to understand what they are going through. If providers can demonstrate empathy and validate the patient’s lived experience, this will go a long way in legitimizing the condition and showing others how complex and life-altering it can be.

Hyperacusis drastically alters people’s lives in multiple ways (published in Jahn et al., 2025). Courtesy of Dr. Kelly Jahn.

Scientific research into hyperacusis is in its infancy, with many unanswered questions. Our recent work suggests that we have a disconnect between researchers, clinicians, and patients. This is not uncommon in the medical field – many chronic health conditions or diseases are incurable, leaving sufferers frustrated and looking for answers. Our lab and many other labs across the world are dedicated to finding answers, converging on a shared understanding of hyperacusis, and supporting those who suffer from the disorder.

Although we are excited about the opportunities to advance the field, we face many challenges that we continually strive to overcome. There are many labs conducting groundbreaking basic science research on hyperacusis, but it is challenging to translate those findings to humans who actually suffer from the condition. We often have trouble finding enough people with pain hyperacusis who are willing or able to participate in clinical studies. Often, the same people participate in multiple studies, and we do not have many new people who want to enroll. It is very important for clinical studies to have a large and diverse group of people so that the findings can generalize to all.

Another challenge is that we don’t have a lot of randomized controlled trials to show that an intervention does or does not work. To my knowledge, there are none that focus specifically on pain hyperacusis. Oftentimes studies will focus on tinnitus as the main problem, with loudness hyperacusis as a secondary measure.

One of our primary goals moving forward is to conduct randomized controlled trials to evaluate potential treatments for people with all subtypes of hyperacusis, including pain. We hope to collaborate with pain researchers who can provide unique insight into the condition and help to design innovative studies using methods that we don’t typically use in the audiology/hearing science space. This may avoid the problem of having to present sound to people who experience sound-induced pain.

Kelly Jahn, AuD, PhD, runs the Neuroaudiology Lab at The University of Texas at Dallas.

Joyce Cohen is a journalist in New York. Owen Llodra is a college student studying speech and hearing sciences.

I suffer with pain hyperacusis (Noxacusis).

I would gladly submit to research groups if it would help bring about a cure!

Hi, I suffer from Hyperacusis and tinnitus. I’d like to help researchers to find a cure.Tnx

The simple and obvious explanation is that “hyperacusis” is due to cochlear hyperactivity,

nothing to do with the brain. In my 1986 paper on Audiosensitivity I showed that this was indeed the case, as there were clear abnomalities in middle-ear muscle reflexes consistent with a drop in perilymph pressure, which in turn can lead to endolymphatic hydrops, as occurs in Meniere’s Disease. This mechanisn can be readily checked by looking for hydrops symptoms in “hyperacusic” patients, especially: ear pressure/fullness; migraine; brain fog; tinnitus; sensitivity to alcohol; giddiness; nausea; diplacusis; memory loss; motion sickness; temporary hearing loss; aggravation by flying; musical hallucinations.

I would be interested to hear from anyone with hyperacusis who has none of the above symptoms.

Well i have hyperacusis and my symptomatic are totally different. And they are: reactive tinnitus, high pitch sounds extremely bothered- some even produce a very bothering high pitch sound that i don’t usually hear, some high pitch sounds for birds not to come nearby that people don’t usually hear i am able to hear and are extreme bothering as well, basic and main thing is high pitch sounds my brain hears distorted and it stresses me out a lot, and they are everywhere soo just somehow existing through all this. Nature and mountains are best relief. But this is it and its alwful, no memory loss and other stuff you mentioned. Distorted sounds and a lot of stress when there they are

I have tinnitus and hyperacusis and have none of the symptoms you just mentioned. What I think is the cause is the inflammation of the original nerve near the ear canal, Muscular bracing of the facial muscles in this area seem to trigger the tinnitus more often . Computer screen are also a trigger for me , again I find the muscles in my face squinting so to speak. Relaxing these muscles through mindful meditation works.

Hi I don’t have all those systems. When I go to a basketball game or swim meet it affects me all over. Takes me days to get over it. I have had to go to a cranial sacral to recover from the loudness. The noise just doesn’t affect my ear. I didn’t know there was a name for this problem. Someone told me to look up pain from noise and this is how I found this site.

Hi Mr.Gordon,

Having Noxacusis since 10 years. I have most of the symptoms you mention. And I am sure pain is developing in the cochlear.

My muscles move around, even in silence. Feels like a hot serum is going out from my cochlea to my ear muscles and to the trigeminal nerve.

Dear Dr.Jahn, I would like participate in any study regarding Hyperacusis.

I suffer Noxacusis since 10 years after a acustica shock in my left ear, right ear is 90%ok.

I live in Austria. I am able to have short video calls.

Please contact me over Email

I have severe Loud Hyperacusis. I’m terrified it is going to turn into Pain Hyperacusis if I don’t protect my ears at all costs. I’m also afraid that overprotecting is going to make my Loud H even worse. I can’t be around my children, with or without protection. It’s too dangerous. I can’t turn on the sink, take a shower, go outside or even open a Ziploc bag without hearing protection. I wasn’t this bad at first until a setback 2 weeks ago. Something has to be done for all of us people suffering. I can’t continue to live like this. Suicide is always running through my mind. There is only so much a human being can take and I am at my wits end.

I have a 30 year old son who has Loud Hyperacusis going on 11 years now. Sadly I watched helplessly as my son deteriorate in life after high school. Eventually he got into drinking alcohol that he said helped him cope with hyperacusis pain symtoms. The drinking alcohol and driving led to involuntary manslaughter. Now he’s in prison. I just wish there was more Dr. Kelly Jahn around in 2014. My heart breaks for all people with Hyperacusis.

stay strong.. Treatments will come soon! Please take care of yourself.. I suffer from severe reactive and polytonic tinnitus and mild hyperacusis..

Sounds for me are painful. Right now, I hear a water tank being filled, with a high motor pitch. This feels like someone lifted my scalp and is rubbing my brain with sandpaper. High-pitched beeps feel like someone is poking my temple with a hot needle. Loud noises feel like someone just hit me on the head. I have had this nearly all my life, but as I get older (I’m in my 60s), it gets worse.