By Frank Magnusson

I am an aerospace engineer and former test pilot with hyperacusis. Hyperacusis is poorly understood, and there is so much conflicting advice that I had to examine it from an engineering problem-solving approach to learn to deal with it on a daily basis.

My hyperacusis — along with tinnitus — started after I sustained a head injury in a high-speed motorcycle accident. I was also diagnosed with a concussion and given no more advice than “It will go away” and then, after six months, “Well, it’s permanent now, learn to live with it.” I have had to do my own research as so many of us have, due to the rarity of this condition and the lack of knowledge among medical professionals.

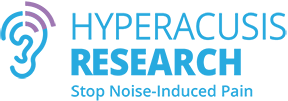

With hyperacusis, everything sounds louder, and I am especially sensitive to high frequencies. I seem to be hearing things 30 to 40 decibels louder, with a spike at higher frequencies. I’ve charted how this feels in Figure 1.

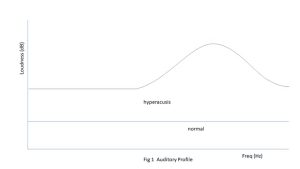

In addition, loud sounds cause a setback, intensifying the other auditory symptoms for some time. For me, it was so bad at the beginning that the sudden sound of a coin dropping on a table would spike my symptoms into orbit for two weeks straight. The volume of sounds would rise seemingly tenfold, and the sensitivity to sounds would worsen by an even greater amount.

Sensitivity to sound is different from increased volume, although they seem to be related. I find that during a setback, the higher frequencies — which are spiked already — spike even further, and cause other symptoms to occur, like ear pain.

But it also seems to me that the frequencies that spike in a setback are related to the frequency of the sound that caused the latest noise insult, whether the same frequency, a band around that frequency or a harmonic of that frequency. It could also be that the frequencies that spike initially and stay there (the spike in Fig. 1) are somehow related to the noise insult that caused the hyperacusis in the first place. A setback feels like Fig. 2.

What about lag, or delayed reaction? At the beginning of my hyperacusis, I would get a setback seemingly out of nowhere. So I started keeping a log of my daily sound exposure and sound insults. I found that the setbacks actually weren’t occurring for no reason. They were all tied to sound events with a very long lag. My first ENT/otolaryngologist told me that typically the inner ear lag is 36-48 hours. In my case it was about four days. Now, the setbacks started making sense.

Over the six years since my injury, the severity of my setbacks and the length of the lag have reduced greatly. Now, it takes louder sounds to cause a setback. My symptoms go up maybe 50%, not 500%, with a lag of about 36 hours rather than four days. It takes a louder noise to cause a setback, like a car horn point blank rather than a coin dropped on a table.

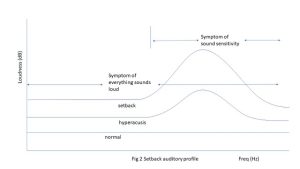

Loudness Discomfort Levels (LDLs), or the loudest sound you can tolerate at a particular frequency, are anything but constant. They vary greatly during the course of a day or week, always dependent upon sound exposure. The time it takes to recover from a setback depends in part on what sound exposure you have when in a setback. There also seems to be a volume level in decibels, different and lower than the LDL, which is the dividing point between loud sounds that cause symptoms to elevate and then lower relatively quickly, versus loud sounds that head into setback territory.

In other words, sounds don’t have to be above your LDL to get a setback. Sounds well below your LDL can cause a setback, as shown in Fig. 3. There really needs to be a new parameter defined to identify the decibel level above which causes a setback — something like Loudness Setback Level (LSL). An example of the variability in daily LDLs is the checkouts beeps at the grocery store. Some days they are well tolerated; other days they are noticeably louder. Sometimes the checkout beeps are so loud that I must wear ear defenders. That’s not the cash register; its my auditory gain that is different on a day-to-day basis.

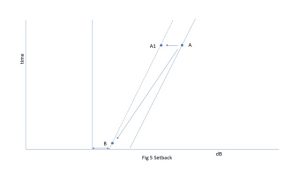

Here are some further insights into describing a setback. If you look at Fig. 5, which is decibels vs. time, you might find yourself at Point A. That line represents the highest decibel level that you can tolerate, and point A is your LDL at that point in time. If you experience a loud sound event, then the line on the right side, representing your sound tolerance, shifts to the left. You find yourself way on the wrong side of the line. You didn’t move; the line did.

You are now way out beyond your new sound tolerance. If you stay there, your tolerance decreases further over time and you can find yourself at Point B. Note that the shape of the curve is like an ice-cream cone. At the top (point A), you have a much wider range of sound tolerance than at point B, where you have a narrow range of tolerance. At point B, you have no room to maneuver and no margin for error; more sound collapses your sound tolerance.

You have to move with the line; i.e. you want to go to Point A1 (lower decibels; less sound) and stay within your new sound tolerance caused by the setback until the setback subsides. This is extremely difficult to figure out. This is also contrary to some of the guidance of Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT) that says if a person with normal hearing isn’t in a noise setting that warrants hearing protection, then you shouldn’t be wearing it either. That guidance is incorrect on several counts. It is based on someone with normal LDLs, which you don’t have, and it does not account for someone who experiences setbacks.

It is also based on the theory that fear is the culprit, which it is clearly not. Once your setback has subsided, then you can start adding more sound back in to go back to where you were at point A.” i.e. you don’t want to stay at point A1; you want to start going back to point A once the setback subsides. See Fig 5.

To reiterate; wrong advice: Don’t wear hearing protection if people with normal ears don’t need to. Better advice: Protect your ears if the sound is loud enough that it will cause a setback or if it will cause your symptoms to elevate badly enough to interfere with your daily activities.

My experience is that you have to back off from sound when in a setback. How much and for how long is completely subjective and tough to figure out since it changes all the time. Continuing to hammer yourself with sound while in a setback doesn’t work. Nor does continuing to do everything you used to do, only with earplugs. Earplugs often aren’t enough.

LDLs are constantly changing due to sound exposure. So it’s extremely difficult to find the right balance of sound enrichment and sound avoidance while trying to live life with the inevitable unpredictable sounds and setbacks that result.

For me, my LDLs vary to the point that I often must cancel plans or errands to let my LDLs recover. I did try wearable sound generators at the beginning when my injury was acute, but my LDLs were so depressed that it was difficult at best and I didn’t get very far. Even on the lowest setting, the generators were too loud while in a setback (which occurred often), which exacerbated the setback and added to the ear pain.

One difficult aspect of hyperacusis is sudden impact sounds: A coin drop, a dog bark, a hammer, a slammed door, a toilet flush, the drumbeat in music, gunfire or sirens on TV. A normal ear seems to have a protective mechanism to dampen that sound so you don’t get the full impact of it. That mechanism doesn’t seem to be working anymore; at least for me. So you get the full brunt of those sounds, which readily cause a setback. The flush of a commercial toilet sounds like a bomb going off. And that is enough to cause a setback.

I hope these insights give you a glimpse into life with hyperacusis with pain and some ideas on hyperacusis management.

Thank you, Frank, for sharing your story, complete with graphs. I have noxacusis and tinnitus, and my experience corrobates strongly with yours.

I am not interested in having TRT because it’s probably too risky for someone like myself. My choice is to desensitize myself to sound at home, and it’s been working out fairly well. I’m not fully recovered, but I’m in a much better place now than I was one year ago when the noise injury occurred.

My fondest wish is to see more scientific interest, research efforts, and funding to go toward the study of hyperacusis, especially noxacusis. Keep sharing your story with others, and maybe this will become a reality someday. It all starts with public awareness.

Thank you very much. I have tinnitus and hyperacusis and your explanation of the variation in sound tolerance was so helpful as well as the unpredictable exposures that caused a setback…the unpredictability of all this is very challenging. Your insights have been very very helpful …

thanks Diane

Thank you

It is true that fear is not the cause of a setback. It’s the other way around. However, science does not want to understand or accept this, resulting in incorrect advice. My hypersensitivity to sound only started four days after attending a concert (just like I read in your story). According to doctors, there was nothing wrong with my hearing. They attributed my symptoms to stress and misdirected attention. End of story. Later, I experienced setbacks several times with also a faster onset and less pronounced symptoms.

But reversing a setback is so difficult (for me, fears are involved after each setback). I read somewhere that setbacks could be the result of an inflammatory response due to overstimulation and insufficient inhibition in the auditory circuits, it could be…

Many thanks for your insights,

Peter

Hi everyone

Your story helped a friend of mine understand better what happens after a setback and that the loudness tolerance level drops. Unfortunately recently i experienced 3 setbacks within a few days. The last 2 i could have prevented. I have to wear double ear protection now in my apartment because I live on a busy street. I can only take them off when the sound is less than 40 db. I am moving in a couple months and it will include a 3 hour plane trip and a 4 hour drive. I know my ear protection won’t be enough. Can anyone suggest how to cope with the intense pain and if it will ever stop? Im very disappointed with my self but somehow have to deal with it. Thank you all

Hey…

I’m experimenting with noise canceling headphones. Sony has some good ones, so does Bose.

The good thing about it is, that one can still listen to audiobooks for example in the loudness one can tolerate, while canceling out all the intolerable sounds from the environment. It’s helpful.